This is a contributed piece by Francois Ajenstat, chief product officer at Tableau Software and has been written in response to a recent piece by our senior staff writer, Dan Swinhoe

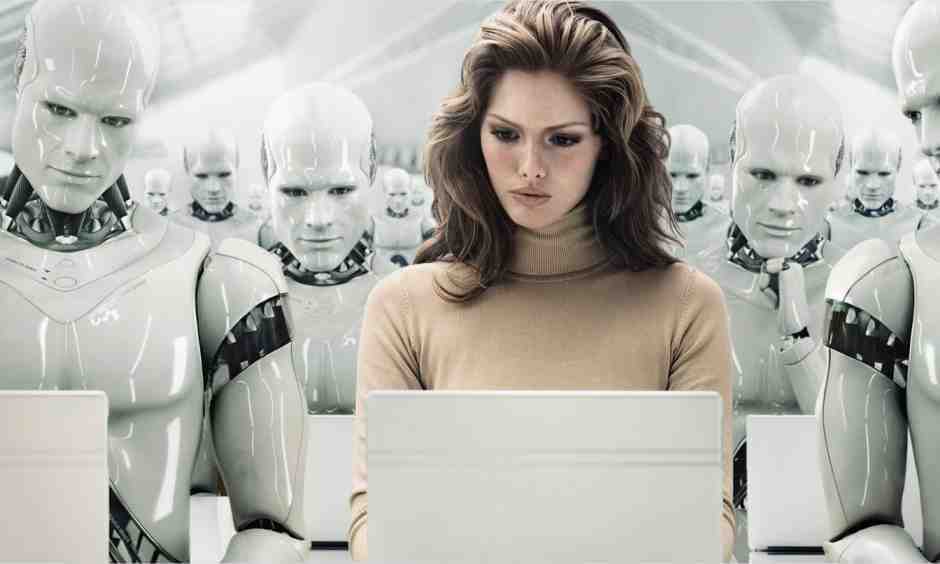

As artificial intelligence surges to the forefront of modern society, research and debate swirls around the power and role it should play. More often than not, a cloud of skepticism looms over the topic of security of jobs in the workforce. However, if we consider AI as assistive intelligence rather than an asteroid on a collision course, humans can take advantage of the opportunities presented through its advancement. With this approach, humans enhance, rather than replace skills, leading to increased benefit from technology and improvements in quality of life.

Applications of AI have the ability to empower workers and increase efficiencies across industries and every aspect of the supply chain. To put this into perspective, a recent study from PwC argues that machines will “increase productivity by up to 14.3% by 2030” and the UK’s GDP could be up to 10.3% higher in 2030, equivalent to an additional £232bn ($307bn).

Yet the advantages of AI are not exclusive to a macroeconomic level. Benefits also extend to the individual level by fundamentally changing employee responsibilities. Workers are liberated from daily mundane and menial tasks to explore a higher level of thinking and creativity, ultimately expanding their job roles. Of course, this in turn will translate into positives for their employers as a more engaged workforce leads to increased sales, productivity and employee retention.

In fact, a recent Deloitte Insights study of workers in the public sector showed that many tasks could actually be handled through automation. The study found that documenting and recording information is the most time-consuming for employees, sucking 10% of work hours, which could be saved using technology like AI.

However, AI is not a replacement for tasks simply because they are time-consuming. The same Deloitte study concludes that tasks, like caring for patients, simply cannot be replaced by AI. For example, cognitive technologies cannot assess a patient’s mood or administer medicine, and therefore are not advanced enough to replace the role of workers carrying out such responsibilities. Currently, the reach of AI extends only to enabling human workers with more of the time and resources needed to provide exceptional patient care. Ultimately, AI compliments human intelligence, enabling workers to focus on tasks that require insights and experience beyond what goes into an algorithm.

This brings us to the fact that true business value comes from the capitalisation of uniquely human skills. Individuals fluent in the language of data are already in high demand across the corporate world. While machine learning backed algorithms and AI assist decision makers in accessing and analysing relevant data, some tasks are abstract or situational and require an amount of intuition and experience to make the best decisions. Humans are uniquely qualified to ensure the encoded assumptions are reasonable and then to ask meaningful follow-up questions that link answers back to business problems.

While AI can find unexpected outliers and identify patterns within the data, human analysis plays a vital role in gathering useful insights from what they find on the screen. This is especially true when those problems lie in industries such as marketing, where success is often related to one’s ability to make a personal connection between brands and consumers – human to human. AI can be used to sort through data and identify a target audience, but only humans have the emotional intelligence to create a story that will resonate with the right audiences and deliver results.

Just as any mammal adapts to a change in its environment, so too will the human race. Machines have yet to match humans in regards to solving contextual business problems with big data. They lack the ability to draw from personal experience, context, emotion and the ingenuity required to go that next step. Exploring this scope is therefore paramount in acquiring job security and increasing workers’ purpose.

The debate surrounding AI will only intensify with its continued expansion. As with any groundbreaking development, the fear of disrupting the status quo is unavoidable. However, disruption does not have to equal destruction.

What matters is how we respond and find new ways to thrive alongside technology.